Jonathan Haidt's "The Anxious Generation"

- Andrew Meunier

- Jan 29

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 18

Jonathan Haidt's newest book has caught the attention of educators, technology skeptics, mental health experts, and parents. There's some evidence that it might be one of those rare books that could actually impact policy in the near future. Haidt has "talked his book" for almost a year now and you can listen to substantive interviews everywhere from New York Times and NPR podcasts to Joe Rogan. For a more adversarial conversation, I recommend Tyler Cowen's interview.

If you've heard anything about "The Anxious Generation," it's likely Haidt's emphasis on the harms of smartphone use among young people. Although he covers some interesting ground in sections about childhood development, free play, and the necessity of in-person interactions for kids (some of my favorite sections were actually about playgrounds!), it's true that Haidt's most arresting data and severe prescriptions involve phone use. They only feel arresting and severe because we adults have our own problematic relationships with the "experience blockers" in our hands and pockets.

Early in the book, Haidt lays out his hypothesis that "The Great Rewiring of Childhood" occurred during the years 2010 - 2015. In his telling, it was during these years that internet-enabled devices became ubiquitous while innovations from technology companies (the "like" button, forward-facing camera, selfie filters, algorithmic feeds, infinite scroll, etc.) changed the landscape of childhood.

Teens today spend about 6-8 hours per day on screens (not counting screens used for schoolwork). In the 1990's, kids spent about 3 hours per day watching TV on average.

Teen smartphone users receive on average about 200 notifications per day.

In 2022, 46% of teens reported being online "constantly."

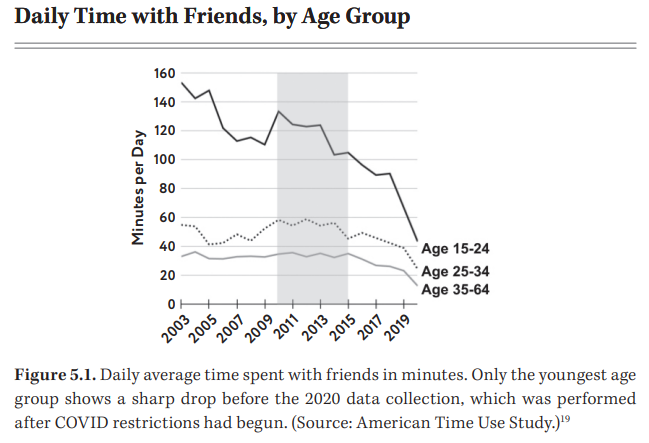

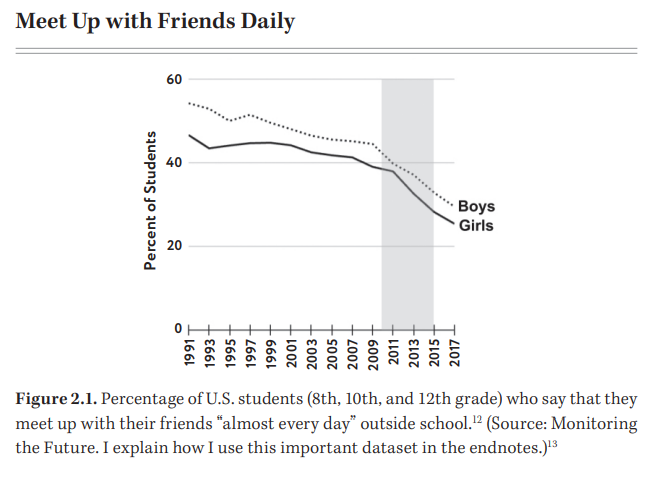

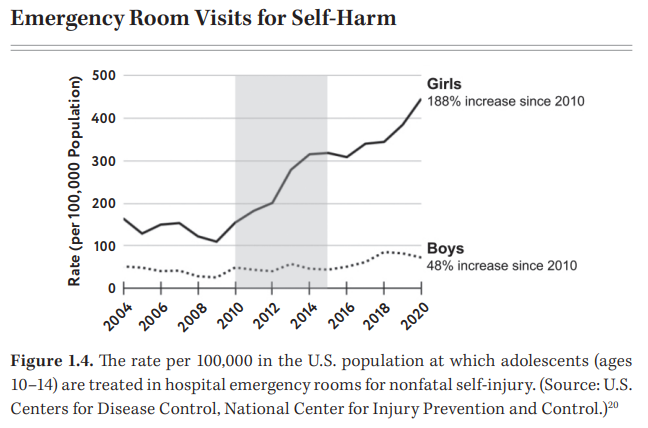

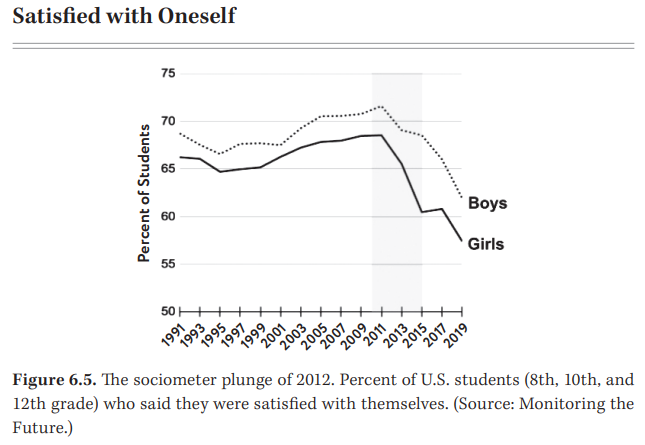

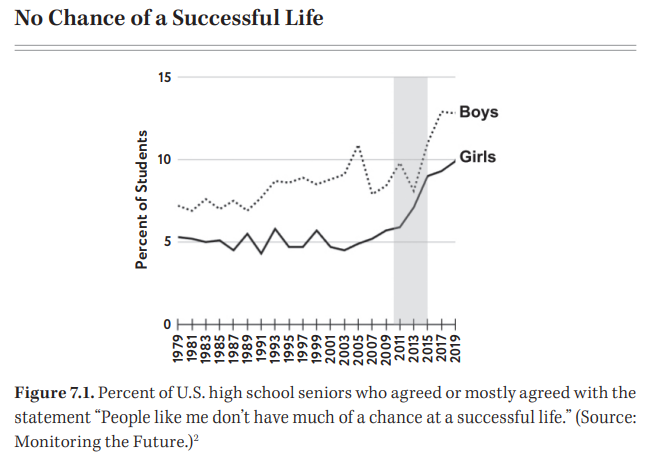

Haidt has helpfully assembled all the charts and illustrations from his book here. In most of them, he highlights his proposed "rewiring" period to draw attention to it (a decision that is illustrative but sometimes feels manipulative). The early chapters focus on a series of concerning trends and findings. The data comes from many sources, including the CDC, the American Time Use Survey, PISA, and the Monitoring the Future survey. There are figures representing data sets from the U.K., Australia, Canada, and other countries, providing some evidence that Haidt's hypothesis applies internationally (or at least in the Anglosphere).

Here are some samples:

Haidt argues that a smartphone-centered childhood is to blame for some of the negative trends he documents. He stitches facts about childhood development together with what we know about how children use smartphones to make a case for how these devices are driving the problem. Here a few "new to me" concepts that I enjoyed thinking about:

Critical period

A period of development when animals are most predisposed to rapidly learn certain skills and habits that then become deep-rooted. There is evidence that children have such a period during roughly ages 9 - 15 where they are wired to be highly attuned to social and cultural lessons.

Conformity bias and prestige bias

Two innate heuristics that people (especially young people) use when socializing. Social media companies have effectively hacked both of these, causing special harm to girls.

"Discover mode" vs. "defend mode"

A play-based childhood cultivates the former. Early and regular exposure to awfulness on the internet encourages the latter and predisposes children (again, especially girls) to disorders like anxiety.

Children are "antifragile"

Children are not only not fragile, but actually require risk and challenge to develop.

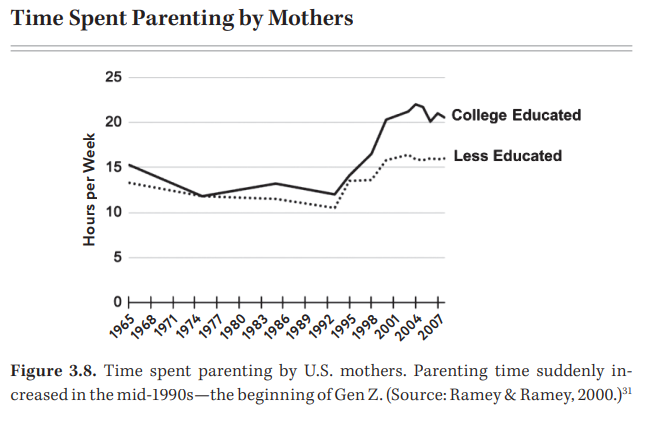

Although Haidt is hard on tech companies and smartphones, a sizable chunk of the book is devoted to other ways that the play-based childhood has been degraded over the course of decades. There is a discussion of changes in parenting and the over-supervision of physical spaces (in contrast to stupefying under-supervision in online spaces).

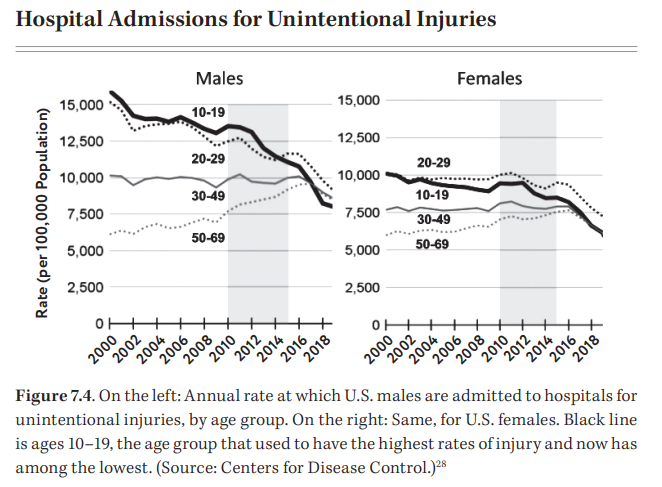

These next three graphs illustrate trends that might seem positive at first, but tell us something profound about how the lives of teens have changed.

Figure 7.4 may be the one I found most surprising in the entire book. Over the course of 18 years, the 10-19 male cohort went from being the most likely to have a serious unintentional injury to the least likely of any age group. Declines in physically risky behavior are good. But these graphs indicate that the lives of teenagers would be unrecognizable to those of the prior generation in a multitude of ways.

Haidt closes the book with prescriptions for cultivating a play-based childhood separate from smartphones. He proposes that social media companies be required by law to take proactive steps to keep children under 16 off of their platforms and assume a legal duty of care. He says that schools should have bans against the use of phones in all settings and that parents should resist giving their students smartphones until they complete middle school (a collective action problem if there ever was one). Not all of his proposals are related to phones– I really liked some of his other ideas for parents and communities, including ways to make it easier to give younger children more freedom (narrowing neglect laws), ideas for encouraging free play, and even some thoughts on playground design.

My experiences with the "anxious generation"

I started teaching in 2008, just before Haidt's Great Rewiring. The infiltration of smartphones into my classroom started around then and almost every student had one by around 2012. I gradually came to realize that my math lessons had to compete with the same variable-ratio reinforcement schedules used in casino games (thanks Meta). There was a period in 2021 - 2022 when my students had an alarming, emotional attachment to their phones (probably stemming from their reliance on them during the pandemic). Fortunately, this has waned somewhat and students don't usually throw a tantrum when we separate them from their phones.

In the last few years, I believe my students have shifted to more overt content consumption– short form videos especially (TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube). I'm not sure if these are more or less insidious than social media, but they are at least as distracting and time-consuming. An almost crippling lack of sleep seems to be the norm now for many of my students.

The newest trend (intensifying since 2022) is students being too anxious or fearful to attend school at all. The result is a slew of students who are either being "homeschooled" or being tutored at my school district's expense. I sympathize with these students and I believe that the adults around them are usually trying to do what is best for them. But the situation doesn't feel healthy or sustainable.

At one point in the book, Haidt mentions another role that phones now play in some households: they are tools that manage and occupy children, keeping them safe at home and away from physical danger. Students receiving text messages from their parents throughout the school day is a normal occurrence now. I'm sure that much of the resistance to changes in school phone policies will come from parents who are accustomed to being in constant contact with their children.

My co-teacher and I rigorously enforce a "no phone" policy in our classroom and have students store their phones in an assigned pocket at the front of the room. Due to this concerted effort and constant vigilance, we have very few issues with phones in our classroom (even though we know many students definitely keep them hidden in their pockets). However, students are still using their phones in the bathrooms (this is prohibited but not enforced), in the hallways (allowed), in the cafeteria (allowed), and in study halls (not really allowed but definitely the norm in certain rooms). Drama stirred up by phone use in school has led to many a physical altercation. And we all know how a smartphone can extend a bathroom visit.

I am in favor of a ban on phones in schools, supported by legislation that protects schools from liability (some of my colleagues are rightly concerned about confiscating $800 devices). Device pouches, like the ones from Yonder, strike me as a ludicrous expense for school districts to absorb just to manage the harm caused by unscrupulous and reckless companies. I wonder if simply having students keep phones in their existing lockers could work just as well. But this would take dedicated enforcement and a commitment on the part of our school and district leaders (again, it's farcical that this is where we need to put our time and energy as educators).

Finally, an aspect of the childhood landscape that Haidt doesn't mention is the almost universal use of 1:1 devices in U.S. schools (we use Chromebooks in my district). Like phones, these have lots of utility and they were certainly useful during the pandemic. However, I increasingly wonder if they are a net gain for students academically. Despite our best efforts, students are easily a few steps ahead of administration when it comes to watching videos, messaging in shared Google Docs (essentially a group text), and playing whatever online game hasn't been blocked yet. Since students can't even go to the bathroom without using their devices to request a pass, these devices are fully entrenched in our educational system. Even as a teacher who uses instructional videos regularly, I sometimes wonder if we'd be better off with a classroom set of devices. In any case, I don't believe we took the plunge into 1:1 devices with eyes wide open and the profit motive for companies like Google is undeniable.

Conclusion

This book is definitely worth reading. There are some really useful suggestions for parents and a powerful call to action for the rest of us. While I believe it's possible that some of the harmful trends discussed in the book were inflamed rather than instigated by the phone-based childhood, I finished the book persuaded that we must make changes to keep our kids healthy and happy. Let me know if you'd like to borrow my copy.

コメント